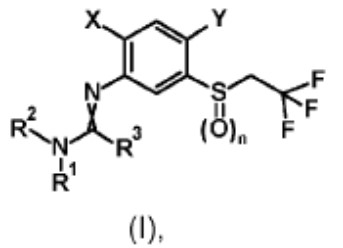

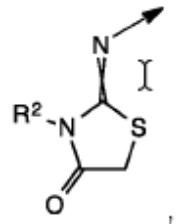

In Ex Parte Mitani, Japan Tobacco took a creative approach in attempting to overcome a non-statutory obviousness-type double patenting rejection before the Patent Trial and Appeal Board: they argued that an improper Markush group rejection during prosecution was tantamount to a restriction requirement, and that it afforded Appellant with “safe harbor” protection under 35 U.S.C.121.

Rather than arguing the merits of the rejection, which was based on an isomeric/close structural similarity relationship between the claimed and the patented compounds, Appellant argued that the Examiner’s improper Markush group rejection, made in the patented case, was a de facto restriction requirement that forced Appellant to prosecute only one of four possible bicyclic substituents. To make them file a terminal disclaimer in a child case in which a different bicyclic structure was being pursued was argued to be unfair.

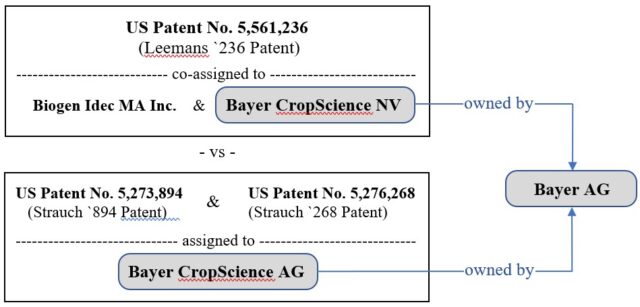

While sympathetic, the Board found itself constrained by the strict guidance given by the Federal Circuit in Geneva Pharms., Inc. v. GlaxoSmithKline PLC, 349 F.3d 1373, 1382 (Fed. Cir. 2003) that “§ 121 only applies to a restriction requirement that is documented by the PTO in enough clarity and detail to show consonance.” Because Appellant did not cite to any documented restriction requirement in the application under appeal (or any application in the chain of priority) between the subject matter claimed and the patented subject matter, and because Appellant did not identify any authority allowing the Board to substitute an improper Markush group rejection for a documented restriction requirement, the Board affirmed the Examiner.

Takeaway: The safe harbor protection under 35 U.S.C. 121 is contingent on a documented restriction requirement in the application under appeal (or any application in the chain of priority) between the subject matter claimed and the patented subject matter. One issue that did not seem to be fully taken into consideration in this appeal was the issuance of an Election of Species requirement in the abandoned parent application, in which the Examiner stated that “each compound is distinct, having different chemical and physical properties, and is made in a different way. In addition, these species are not obvious variants of each other based on the current record.” Because no prior art was used in the double patenting rejection, this statement of patentable distinctness should still apply.

Judges: E. Grimes, R. Lebovitz, F. Prats