When considering the obviousness of ranges, it is a fundamental principle of U.S. patent law that “where the general conditions of a claim are disclosed in the prior art, it is not inventive to discover the optimum or workable ranges by routine experimentation.” In re Aller, 220 F.2d 454, 456 (CCPA 1955). Consequently, modifications to readily optimized parameters such as temperatures and concentrations disclosed in the prior art will generally not be patentable under Section 103. Aller, 220 F.2d at 456. Furthermore, a presumption of obviousness exists when ranges disclosed in the prior art overlap with the ranges of a claimed invention. See, e.g., E.I. du Pont de Nemours & Company v. Synvina C.V., 904 F.3d 996, 1006 (Fed. Cir. 2018).

On July 14, 2020, the Patent Trial and Appeal Board issued a decision in Ex parte Park (Appeal 2019-006050) in which a rejection over an overlapping prior art genus was determined to be insufficient to establish a prima facie case of obviousness under both a lead compound analysis and an obvious equivalents/overlapping genus analysis. In addition, the Examiner’s initial rejection of subject matter beyond the elected specie was determined to be a withdrawal of the election requirement.

On August 19, 2020, the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“Board”) issued a decision in Ex parte Boutillier (Appeal No. 2020-000348) reversing an Examiner’s obviousness rejection for failing to establish that the prior art inherently taught a claimed property.

The independent claim in Boutillier required a composition that included an elastomeric phase formed of a block copolymer, where the block copolymer had “a water solubility of less than 0.5 g/l.”

The prior art cited by the Examiner disclosed water soluble block copolymers that could be formed from the same monomers and in the same proportions recited in the Applicant’s dependent claims (e.g., acrylic and/or methacrylic monomers). Although the prior art did not disclose the water solubility of the block copolymer, the Examiner reasoned that “[the] instantly claimed water solubility can be made from the disclosure of [the prior art]” because the copolymer of the prior art “can include the same monomers as instantly claimed, within the same weight ranges as instantly claimed.”

The Applicant disagreed with the Examiner’s reasoning because the block copolymers of the prior art were characterized as being water soluble, and thus, would not be expected to have a water solubility less than 0.5 g/l.

The Board sided with the Applicant. The Board found that even though it was undisputed that the prior art taught block copolymers that could be prepared from the same monomers claimed by the Applicant, the prior art expressly taught its block copolymers were water soluble. The mere fact that it might be possible to prepare a block copolymer with a water solubility of less than 0.5 g/l with the monomers disclosed in the prior art was insufficient to establish the inherency of this feature.

The Board emphasized that the “very essence of inherency is that one of ordinary skill in the art would recognize that a reference unavoidably teaches the property in question.” Agilent Technologies, Inc. v. Affymetrix, Inc., 567 F.3d 1366, 1383 (Fed. Cir. 2009). And, in this case, the water solubility of less than 0.5 g/l was not “unavoidable or the natural result following [the prior art’s] teaching.”

Takeaway: Examiners often rely on the rationale that “if the prior art teaches the identical chemical structure, the properties applicant discloses and/or claims are necessarily present.” In re Spada 911 F.2d 705 (Fed. Cir. 1990). However, this rationale breaks down in two situations. The first is where there is a broader teaching in the prior art, as in this case, that suggests the property would not necessarily be present despite similarities in the chemical structures. The second is where there is a generic disclosure in the prior art that encompasses–but does not specifically teach–the identical structure claimed. In this situation, a presumption of inherency can be rebutted by showing that one or more species falling within the generic disclosure do not exhibit the claimed property.

Judges: E. Grimes, F. Prats, L. Ren

On July 31, 2020, the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“Board”) issued a decision in Ex parte Marco (Appeal No. 2020-000873) reversing an Examiner’s rejection for failure to comply with the written description requirement.

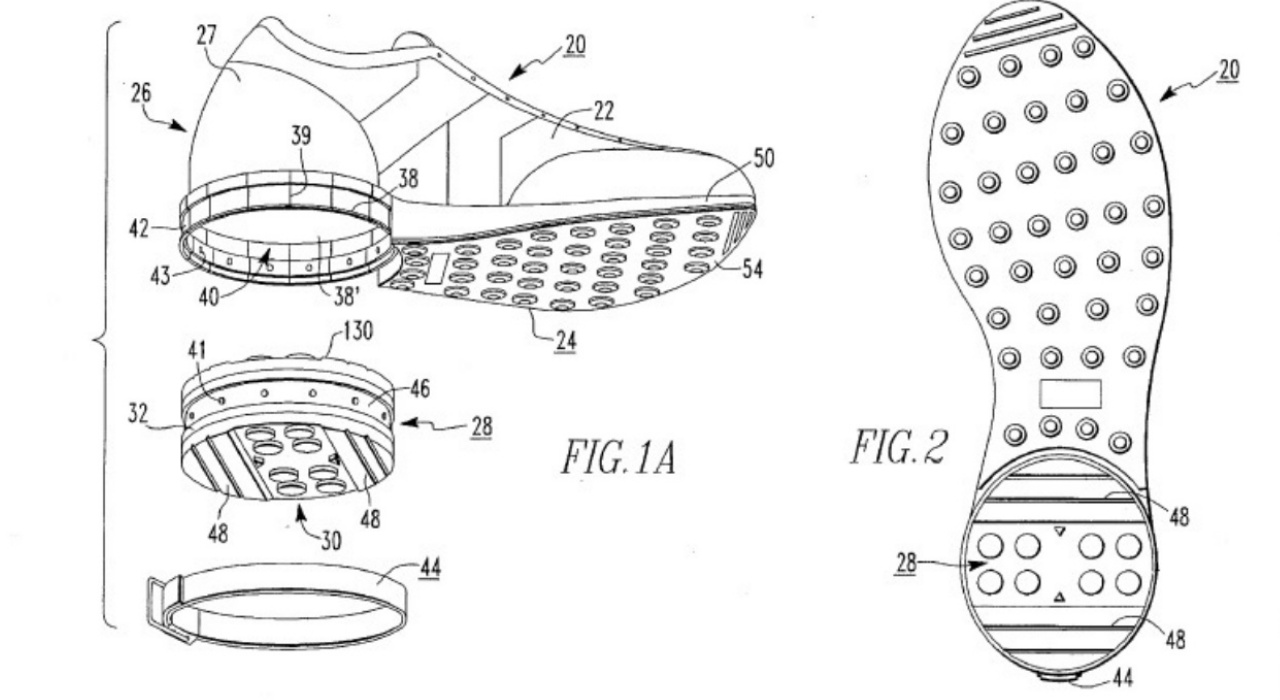

The written description controversy in Marco centered on a requirement in claim 2 for a hat having an opposing pair of under-chin straps that were “at least about one inch in width.” According to the Applicant, the width of “at least about one inch” was supported by the original specification, particularly the embodiments illustrated Figures 5 and 7 (shown below):

Patent claims often recite structural limitations in combination with one or more properties. For example, a product claim might recite a composition comprising three components, where one of the components is specified as having certain physical properties. In such cases, U.S. patent examiners often reject the claims as either anticipated or obvious based on prior art describing the structural limitations but not describing the properties.

On July 16, 2020, the Federal Circuit issued a decision in Akeva L.L.C. v. Nike, Inc., Addidas America, Inc. (nonprecedential) in which the difference between removing a subject matter disclaimer from the specification, as opposed to removing one made in amendments and/or remarks during prosecution, amounted to the difference between winning and losing.

In assessing the obviousness of chemical species when prior art teaches an encompassing genus, Section 2144.08 of the MPEP advises us to consider any teaching or suggestion in the reference of a preferred species or subgenus that is significantly different in structure from the claimed species or subgenus—because such a teaching may weigh against selecting the claimed species or subgenus. See M.P.E.P. § 2144.08, para. II.A.4(c).

On July 1, 2020, the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“Board”) issued a decision in Ex parte Allen reversing an Examiner’s obviousness rejection for failing to provide sufficient reason based on rational underpinning to combine the teachings of the prior art. See Decision on Appeal, Appeal No. 2018-008208, at 6 (P.T.A.B. Jul. 1, 2020) (non-precedential).

Allen represents a common scenario encountered during prosecution; namely, where an Examiner relies on a secondary reference to teach elements missing from the primary reference based on an illusory or non-existent problem in the primary reference.

The independent claim in Allen recited a method for introducing a cable into a conduit by attaching a pliant material to the cable with an adhesive and then introducing the cable/pliant material into the conduit, where the pliant material exhibited less friction than the cable. See id. at 2 (claim 5).

The Examiner rejected the claims over a combination that included Conti (US 5,027,864), which disclosed a method of introducing a cable into a conduit but lacked the pliant material attached to the cable with adhesive, and Holland (US 2002/0170728), which disclosed attaching a pliant material to a cable with an adhesive “to mak[e] a cable abrasion-resistant … when being moved or pulled.” Id. at 4 (emphasis added). According to the Examiner, it would have been obvious to modify Conti to include the pliant material and adhesive of Holland for the purpose of making the cable abrasion resistant.

The Appellant disagreed because Conti already recognized the friction problem when inserting the cable into the conduit and solved it by applying a lubricant to the cable. Nevertheless, the Examiner speculated that “in practice[,] lubricated systems are not always perfectly lubricated due to inhibited lubricant flow and/or improper maintenance of the fluid within the passage/channel” and, in that scenario, the skilled artisan would “look to supplemental means for protecting the cable within the tube/duct.” Id. at 6.

Rejecting the Examiner’s rationale, the Board highlighted Conti’s teaching that “[t]he presence of lubricant on the cable greatly reduces friction and thus the pulling force required to install the cable.” Id. at 4. Given Conti’s teaching to continuously feed the lubricant to reduce friction and the pulling force required to install the cable, the Board failed to see why it would have been obvious to combine Conti’s lubricated cable to include a pliant material from Holland’s unlubricated system or how such a combination would resolve the speculative problems alleged by the Examiner (i.e., to make Conti’s cables more friction resistant and/or further protect Conti’s cable within the conduit).

Takeaway: Examiners often formulate a problem in the primary reference that can be solved by a secondary reference, thereby providing the motivation for combining the references to arrive at the claimed invention. However, when the problem is already solved by the primary reference, there may be no motivation to combine the references, even when the Examiner resorts to allegations that secondary reference can “further improve” upon the primary reference (e.g., to make Conti’s cable more friction resistant). Allen provides a good illustration of this scenario and the importance of assessing problem/solution motivations to determine whether the alleged problem is illusory or non-existent.

Judges: C. Greenhut, A. Reimers, S. Mitchell

A rejection for obviousness must include “some articulated reasoning with some rational underpinning to support the legal conclusion.” KSR Int’l Co. v. Teleflex Inc., 550 U.S. 398, 418 (2007) (quoting In re Kahn, 441 F.3d 977,988 (Fed. Cir. 2006)). In Ex parte Awan, by reversing the Examiner’s obviousness rejection, the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“Board”) reconfirmed the necessity of articulated reasoning with rational underpinning in an obviousness rejection.

On May 13, 2020, the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“Board”) issued a decision in Ex parte Ismagilov reversing an Examiner’s rejection of original claims for failing to comply with the written description requirement.