When considering the obviousness of ranges, it is a fundamental principle of U.S. patent law that “where the general conditions of a claim are disclosed in the prior art, it is not inventive to discover the optimum or workable ranges by routine experimentation.” In re Aller, 220 F.2d 454, 456 (CCPA 1955). Consequently, modifications to readily optimized parameters such as temperatures and concentrations disclosed in the prior art will generally not be patentable under Section 103. Aller, 220 F.2d at 456. Furthermore, a presumption of obviousness exists when ranges disclosed in the prior art overlap with the ranges of a claimed invention. See, e.g., E.I. du Pont de Nemours & Company v. Synvina C.V., 904 F.3d 996, 1006 (Fed. Cir. 2018).

One way to rebut the presumption of obviousness based on overlapping ranges is to show that the claimed parameter was not recognized by as being “result-effective,” i.e., a variable which achieves a recognized result. Synvina, 904 F.3d at 1006 (citing In re Applied Materials, Inc., 692 F.3d 1289, 1295 (Fed. Cir. 2012)).

In the latest revision of the Manual of Patent Examining Procedure (“MPEP”), released in June 2020 (Ninth Edition, Revision 10), Section 2144 includes a new sub-section describing the framework for rebutting obviousness rejections by showing that a claimed parameter was not recognized as being “result-effective.” Drawing heavily from the Court’s opinion in Synvina, Section 2144.05, para. III.C of the MPEP reads as follows:

C. Showing That the Claimed Parameter Was Not Recognized as “Result-Effective”

Applicants may rebut a prima facie case of obviousness based on optimization of a variable disclosed in a range in the prior art by showing that the claimed variable was not recognized in the prior art to be a result-effective variable. E.I. Dupont de Nemours & Company v. Synvina C.V., 904 F.3d 996, 1006 (Fed. Cir. 2018). (“The idea behind the ‘result-effective variable’ analysis is straightforward. Our predecessor court reasoned that a person of ordinary skill would not always be motivated to optimize a parameter ‘if there is no evidence in the record that the prior art recognized that [that] particular parameter affected the result.’ Antonie, 559 F.2d at 620. For example, in Antonie the claimed device was characterized by a certain ratio, and the prior art did not disclose that ratio and was silent regarding one of the variables in the ratio. Id. at 619. Our predecessor court thus reversed the Board’s conclusion of obviousness. Id. at 620. Antonie described the situation where a ‘parameter optimized was not recognized to be a result-effective variable’ as an ‘exception’ to the general principle in Aller that ‘the discovery of an optimum value of a variable in a known process is normally obvious.’ Id. at 620. Our subsequent cases have confirmed that this exception is a narrow one. … In summarizing the relevant precedent from our predecessor court, we observed in Applied Materials that ‘[i]n cases in which the disclosure in the prior art was insufficient to find a variable result-effective, there was essentially no disclosure of the relationship between the variable and the result in the prior art.’ 692 F.3d at 1297. Likewise, if the prior art does recognize that the variable affects the relevant property or result, then the variable is result-effective. Id. (‘A recognition in the prior art that a property is affected by the variable is sufficient to find the variable result-effective.’)”). Applicants must articulate why the variable at issue would not have been recognized in the prior art as result-effective.

A recent decision from the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“Board”) illustrates that adequate recognition in the prior art must be based on a clear nexus between the claimed parameter and the “relevant property or result”—and should not be based on other cause-and-effect relationships that could necessarily lead to the claimed parameter through routine optimization.

On July 2, 2020, the Board issued a decision in Ex parte Morey reversing obviousness rejections based in part on a purported result-effective variable. In this appeal, the applicant persuaded the Board that the claimed parameter at issue was not a recognized result-effective variable, because the cited prior art did not recognize a clear nexus between the claimed parameter and the relevant property.

The claims at issue in Morey relate to strengthened glass articles having a “stress profile” that improves the “frangibility” characteristics of the glass articles. Claim 5 of the relevant application, with emphasis on the relevant limitation, reads as follows:

5. A strengthened glass article comprising:

a thickness t ≤ 1 mm,

an inner region under a central tension CT, and

at least one compressive stress layer adjacent the inner region and extending within the strengthened glass article from a surface of the strengthened glass article to a depth of layer DOL, wherein the DOL is greater than or equal to70 μm,

wherein the strengthened glass article is under a compressive stress at the surface CSs,

wherein the strengthened glass article is an alkali aluminosilicate glass article comprising 0 mol% Li2O, and at least 3 mol % Al2O3, and

wherein the strengthened glass article has a stress profile such that a compressive stress CSD at an intermediate critical depth of 50 μm below the surface of the strengthened glass article is at least 10% of CSs.

Appeal No. 2018-005633, at 3 (P.T.A.B. July 2, 2020) (non-precedential) (emphasis added).

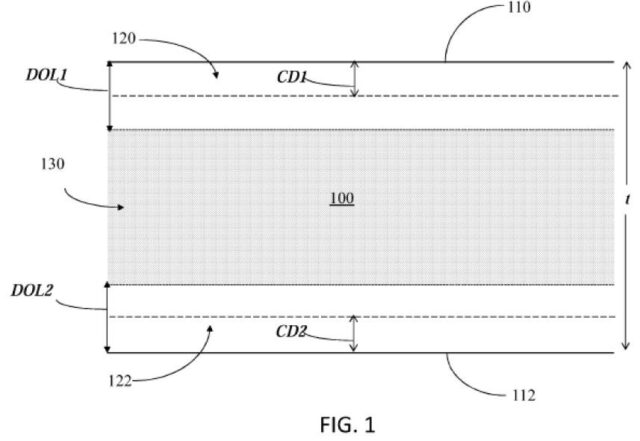

Figure 1 of the relevant application, shown below, illustrates the first and second “surfaces” (110, 112), the first and second “compressive stress layers” (120, 122), the “inner region” (130), the “depths of layers” DOL1 and DOL2, and the “intermediate critical depths” CD1 and CD2.

Regarding the “stress profile” limitation in Claim 5, the relevant application discloses that the intermediate critical depths CD1 and CD2 and the compressive stresses at these critical depths are sufficient to increase the survivability of the inventive glass article (100) by enveloping or encasing a flaw introduced by a sharp impact to the first and second surfaces (110, 112).

To account for the required “stress profile” of Claim 5, the Patent Office relied upon the teachings of US 2010/0035038, published by Barefoot et al. (“Barefoot”), which the Examiner acknowledged fails to explicitly recognize the effect of the “stress profile” limitation in Claim 5 on the frangibility of the glass article.

The Examiner argued that the “stress profile” of Claim 5 was implicitly recognized to be a result-effective variable because, based upon the teachings of Barefoot, persons of ordinary skill in the art would understand that optimizing the depth of layer DOL and/or the compressive stress at the surface CSs could lead to strengthened glass articles with improved frangibility. As explained in the Examiner’s Answer:

Barefoot indicates the DOL and CSs [(i.e., compressive stress at the surface of the glass article)] of a strengthened glass article generally dictate the frangibility of the strengthened glass article as can be determined by, for instance, point impact testing and are dependent upon the process used to strengthen the glass article . . . . Additionally, given frangible behavior is the result of excessive CT within a strengthened glass article . . . , one of ordinary skill in the art would appreciate increasing at least one of the DOL and/or CSs in a strengthened glass article would improve the resistance to fracturing or cracking.

Appeal No. 2018-005633, at 5.

The Examiner argued that “DOL and CSs, and therefore CSD (which depends on the DOL and CSs) and CT, are optimizable, result-effective variables for obtaining a strengthened glass article with low frangibility achieved by varying parameters known to those of ordinary skill in the art.” Id.

Based on those findings, the Examiner concluded that it would have been obvious to one of ordinary skill in the art to modify Barefoot’s strengthened glass article to have a compressive stress CSD as claimed by increasing at least one of the DOL and CSs to provide a strengthened glass article which is low in frangibility.

The Board, on the other hand, agreed with the applicant’s argument that there is no teaching or suggestion in the cited art that the CSD-to-CSs relationship (i.e., the “stress profile”) in Claim 5 affects the frangibility of the strengthened glass article. As explained by the Board:

The Appellant argues that “there is no teaching or suggestion in Barefoot or Allan that the CSD to CSs relationship affects frangibility.” Br. 7. Therefore, the Appellant argues that the rejection on appeal is based on impermissible hindsight. Br. 8.

The Appellant’s argument is persuasive of reversible error. Barefoot discloses that the observed differences in behavior between a glass plate which exhibits frangible behavior and a glass plate which exhibits non-frangible behavior can be attributed to a difference in central tension CT. Barefoot ¶ 25. The Examiner finds that “[s]ince CSD depends on DOL and CSs and CSs is related to CT, it follows that CSD, and therefore the relationship of CSD to CSs, is related to frangibility.” Ans. 19. Based on those relationships, the Examiner explains that DOL and CSs, as result-effective variables, “are modified to give the claimed CSD.” Ans. 20. The Examiner, however, has failed to show that optimizing DOL and CSs to provide a strengthened glass article having a desired frangibility as disclosed in Barefoot would necessarily result in the claimed CSD. See Br. 8 (arguing that the Examiner has not established a connection between frangibility and the claimed CSD to CSs relationship). For that reason, the obviousness rejection is not sustained.

Appeal No. 2018-005633, at 7 (emphasis added).

Takeaway: When an obviousness rejection is premised upon a claimed parameter being a result-effective variable, the rejection should be scrutinized to determine whether the cited art recognizes a clear nexus between the parameter and the relevant property or result.

Judges: A.L. HANLON, J.R. SNAY and M.C. CASHION, Jr. (Opinion by HANLON)