In Ex parte Johnson, the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“Board”) rejected an Examiner’s construction of a claim term because it conflicted with the meaning given in other patents from analogous art.

The claims on appeal in Johnson were drawn to a prosthetic heart valve including, inter alia, a “cloth-covered undulating rod-like wireform.” Appellant’s specification defined the term “wireform” as “an elongated rod-like structure formed into a continuous shape defining a circumference around a flow orifice for supporting flexible leaflets in the various prosthetic valves herein.” See US 2017/0239044, ¶ [0041].

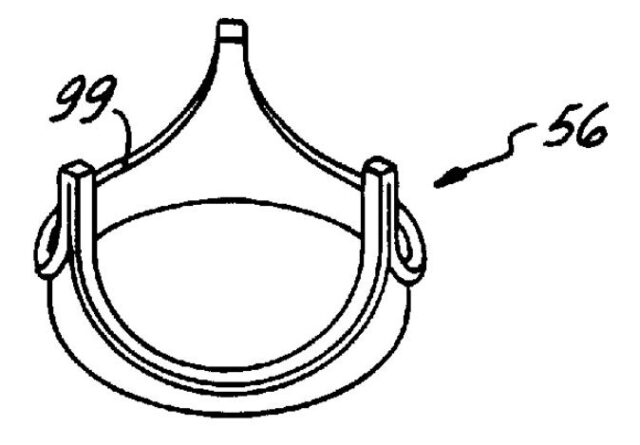

In rejecting the claims as anticipated by US 5,928,281 (“Huynh”), the Examiner relied on element 99 of Huynh, which is shown below and linked here for convenience:

Applying the broadest, reasonable interpretation and relying on a dictionary published in 2020, the Examiner found that element 99 of Huynh was a rod-like wireform because it had “an elongated structure with a shape similar to a stick, wand, staff, or the like.”

Appellant disagreed with the Examiner’s construction, arguing element 99 of Huynh referred to a cloth top edge of a stent assembly rather than an “undulating rod-like wireform formed into a continuous shape having alternating cusps and commissures around a periphery.” Appellant’s argument was supported by Huynh’s description of element 99 as an “upper surface 99 (see FIG. 1) of [the] stent” and Huynh’s use of the term “wireform” elsewhere to refer to a “wire” or “wire-like” structure. Appellant’s construction was also consistent with the description of “wireform” in two separate analogous references to mean a bent “wire” structure (US 6,539,984 B2, issued Apr. 1, 2003) and a bent, machined, or molded “wire-like” structure (US 7,871,435 B2, issued Jan. 18, 2011).

Rejecting the Examiner’s construction as unreasonably broad, the Board noted:

It is well settled that prior art references may be indicative of what all those skilled in the art generally believe a certain term means . . . [and] can often help to demonstrate how a disputed term is used by those skilled in the art. Accordingly, the PTO’s interpretation of claim terms should not be so broad that it conflicts with the meaning given to identical terms in other patents from analogous art.

Relevant to the Board’s decision were the contemporaneous patents and even the prior art relied on in the rejection, all of which were consistent with Appellant’s specification and construction.

With Huynh lacking the claimed cloth-covered undulating rod-like wireform, the Board reversed the anticipation rejection.

Takeaway: While it can be difficult to rebut an Examiner’s unreasonably broad construction of a claim term when the specification does not define, or does not sufficiently define, the claim term in question, valuable rebuttal evidence may be found in contemporaneous publications. As shown in Johnson, the Board found the consistent usage of the claim term in three analogous publications (including the allegedly anticipating reference) trumped the Examiner’s construction based on a generic dictionary definition. This is not to say dictionaries are always a poor source of evidence, but dictionaries typically include multiple definitions and a general definition may not accurately reflect how the claim term is used in the relevant art.

Judges: S. Staicovici, E. Brown, W. Capp

by Beau Burton

Beau B. Burton, Ph.D., was a founding partner of Element IP. His practice focused on patent procurement, post-grant proceedings, including inter partes reviews (IPRs) and ex parte re-examination, and patent validity and infringement opinions.

One comment

Pingback: 特許庁による審査においてクレーム用語の解釈が既存技術における意味と矛盾してはならない - Open Legal Community

Comments are closed.